Fen Stanton: Watercolour (1941) by Edward Walker at The V&A

Fenstanton is a village in the historic county of Huntingdonshire (now in Cambridgeshire), to the south of St Ives. Its two most famous residents have been Lancelot “Capability” Brown, a renowned landscape architect and gardener, and John Howland, one of the Pilgrims who sailed on the Mayflower.(1) Fenstanton was also the site of a Roman settlement circa 100-400 AD. Here, archaeologists recently unearthed the skeleton of a man with a nail through his heel, who had been crucified as a form of punishment and death. This article from the BBC shows a facial reconstruction of the crucifixion victim. Could this be one of my ancestors?(2)

Phillip Allpress: Fenstanton farmer

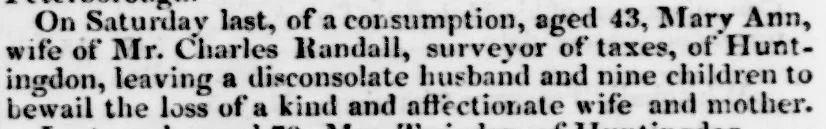

My 4th great-grandmother Mary Ann Allpress (1786-1830), who married Charles Randall in 1812, was born in Fenstanton. She was the daughter of Phillip Allpress (1753-1838), a farmer, and his wife Elizabeth Taylor (1764-1843). Phillip and Elizabeth were married in August 1786, and they baptised their first child Mary Ann in December. (3, 4) I think it’s safe to say they “knew” each other before their wedding. Phillip and Elizabeth went on to baptise 11 more children in Fenstanton: Elizabeth (born 1788), Sarah (born 1789), Thomas (born 1790), John (born 1792), Phillip (born 1794), John (born 1796), Robert (born 1797), Catherine (born 1799), Rivers (born 1802), William (born 1804), and George (born 1806).(5)

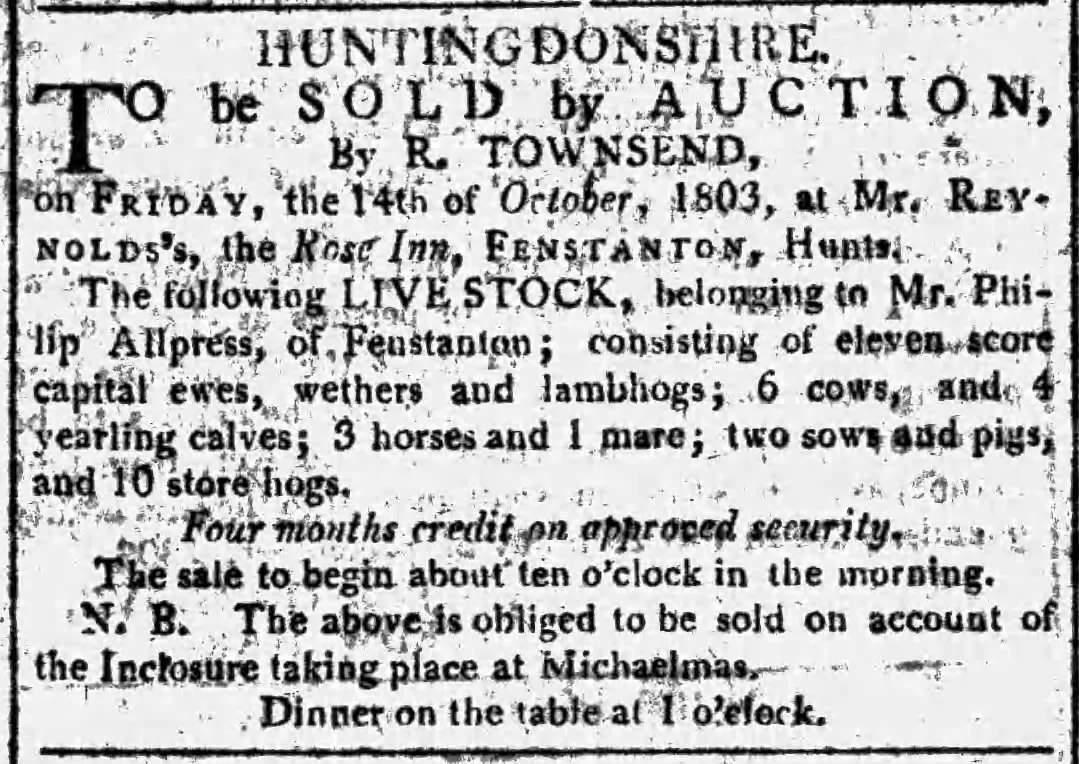

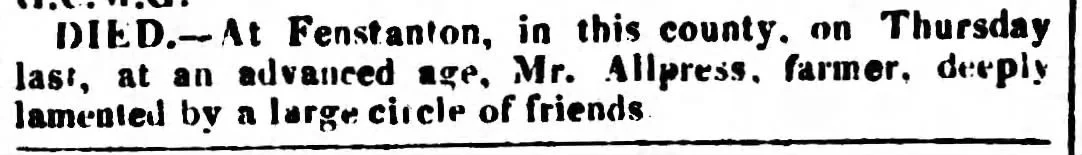

In 1803, Phillip Allpress had to sell his livestock due to an inclosure act passed by Parliament the previous year.(6) These acts converted common lands and open fields into private enclosures.(7) Phillip had to part with 220 sheep, 6 cows, 4 calves, 3 horses, 1 mare, 2 pigs, and 10 hogs. I’m not sure whether this was most of his livestock or just a portion of it, but the sale gives us some insights into his farming operation. His death notice, published in 1838, suggests that he was a well-liked and well-respected man.(8)

Livestock auction advertised in the Cambridge Chronicle and Journal, 8 October, 1803

Phillip’s death notice in the Huntingdon, Bedford, & Peterborough Gazette, 17 March, 1838

Tracing the Allpress surname

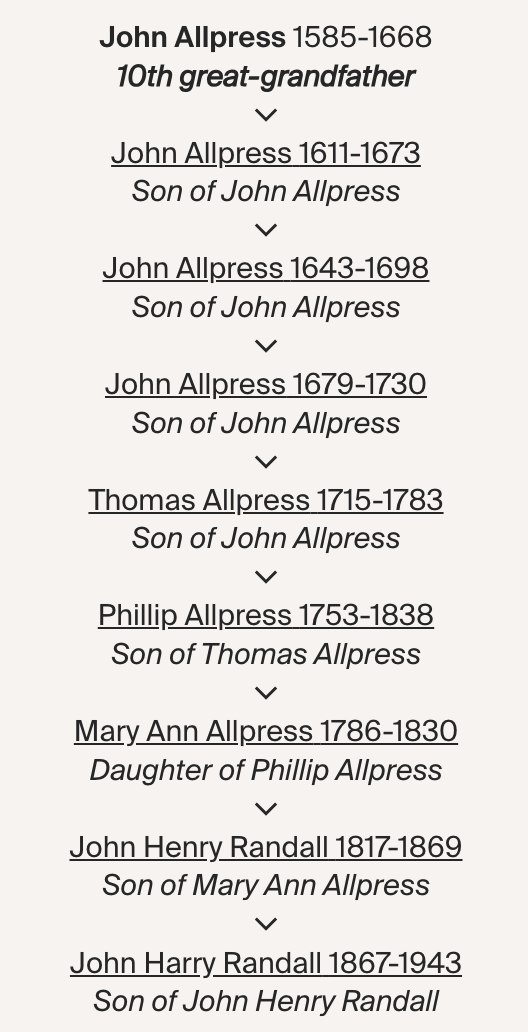

Phillip’s wife Elizabeth was originally from Ely, but Phillip’s family had been in Fenstanton since at least the early 1600s. I haven’t done a proper One-Name Study on his surname (I may in the future), but the Allpress name has been one of the easier names to research in my tree. All lines seem to go back to Huntingdonshire, with the earliest mentions of Allpress (sometimes spelled Alpress) recorded in Fenstanton in the early Jacobean era. According to the Bishop’s Transcripts (9), John Allpress married Joane Hutton on the 9th of February, 1605/6, in Fenstanton. I believe this couple are my 10th great-grandparents, but the further back I go the less confidence I have due to missing records. I have not been able to find a will for this John Allpress (died 1668), his first wife Joane (died 1619), or their presumed son John Allpress (died 1673). But I have found wills for various other Allpress men of Fenstanton. I believe the line leading to my ancestor Phillip Allpress (and beyond) is as follows:

My Allpress to Randall line (Note: birth years are approximate when baptism records could not be found)

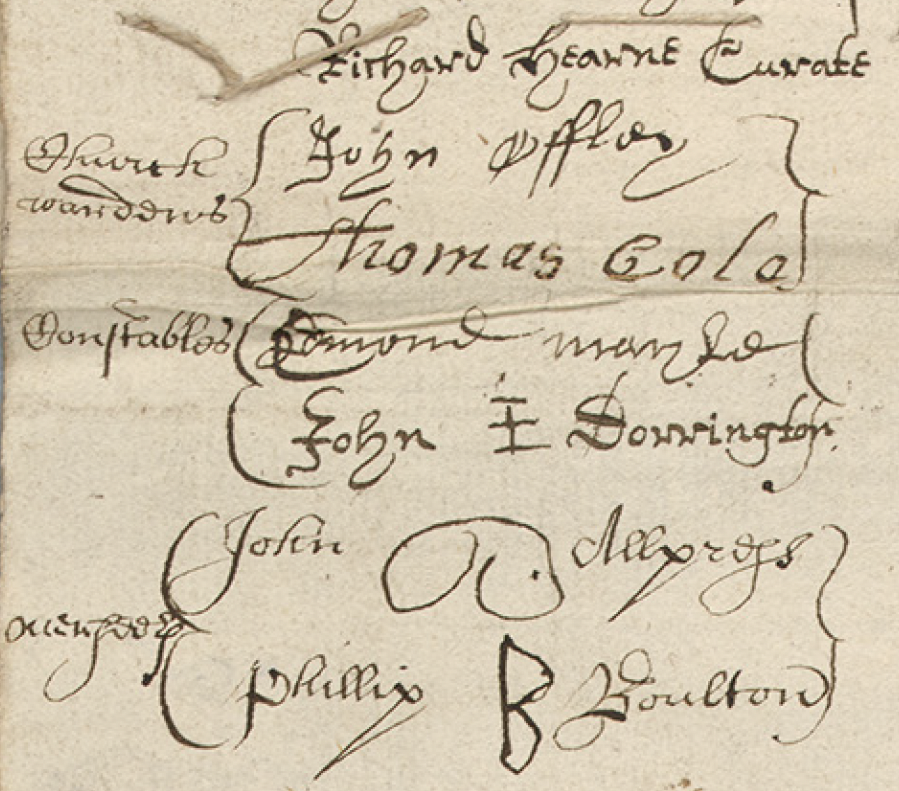

Protestation Returns

The name Allpress appears in the Protestation Returns of 1641-1642 for the parish of Fenstanton. These documents listed the adult males in England who took an oath "to live and die for the true Protestant religion" prior to the start of the English Civil War.(10) Only one-third of the lists survive. The images were previously hosted at the UK Parliamentary Archives, but those links are now dead as the collections are moving over to the UK National Archives at Kew.(11) Luckily, I downloaded the images previously and can show you some screenshots here.

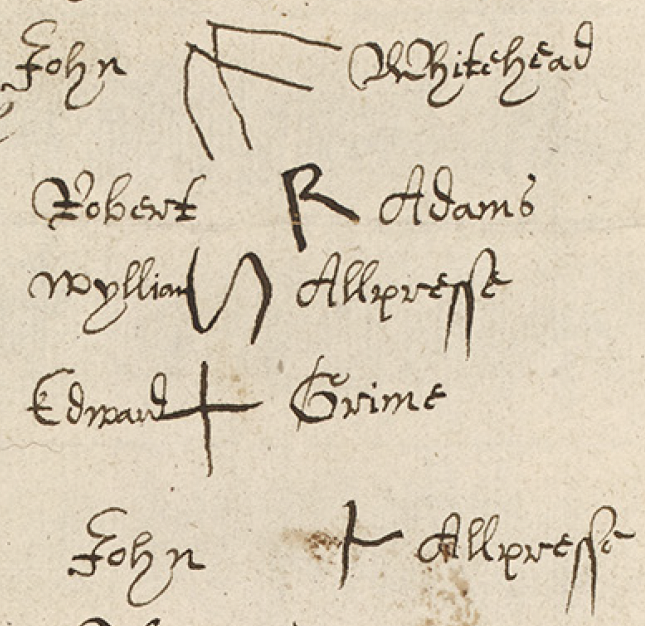

Excerpt from the Protestation Return for Huntingdonshire, Toseland Hundred, Fen Stanton (1641-1642). I think the mark of John Allpress, overseer, looks like a pair of spectacles. What do you think?

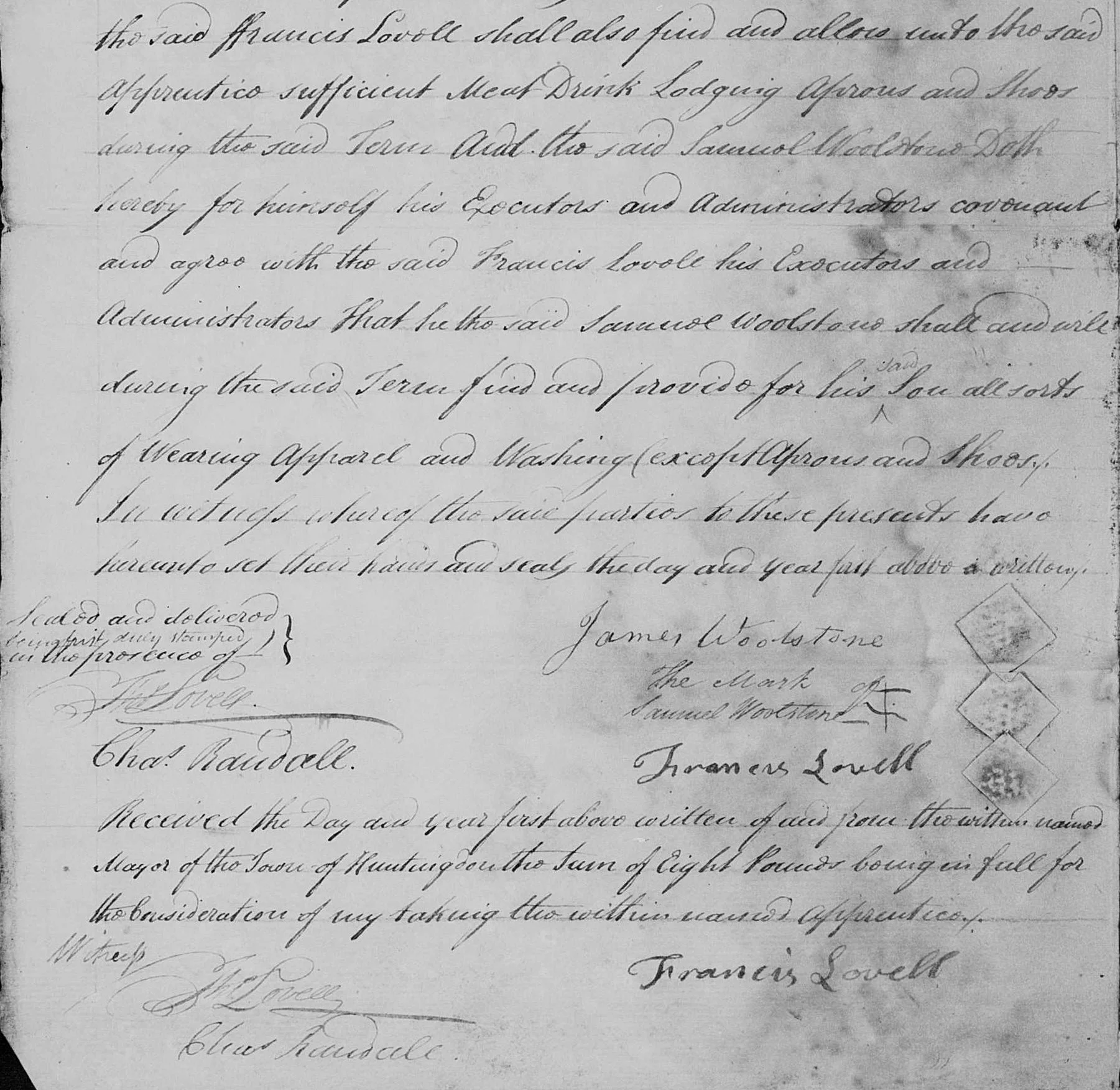

The list for Fenstanton is in great condition. The majority of the men made a mark for their name rather than signing. The list includes two men named John Allpress. Based on available parish records and wills, I think the one named as an overseer of the parish is the man who died in 1668 (my 10th great-grandfather), while the other John is the man who died in 1673 (my 9th great-grandfather).

The list also includes Henry Allpress (probably the one who died in 1651), Myles Allpress (probably the one who died in 1673), William Allpress (probably the one who died in 1697), and two men named Thomas Allpress (one of these men died in 1664; I can’t find a burial for the other Thomas).

Excerpt from the Protestation Return for Huntingdonshire, Toseland Hundred, Fen Stanton (1641-1642) featuring the marks of Wylliam (William) and John Allpress

Allpress today

Nowadays, if you search on the name Allpress in Google most results will be for Allpress Espresso, a coffee company started in New Zealand by Michael Allpress. Michael is the son of the late actor Bruce Allpress, who starred in The Lord of The Rings: The Two Towers.(12) I haven’t been able to link this Allpress line to my tree (yet), but surely we are distant cousins?

Do you have the surname Allpress in your family tree? I’d love to hear from you! I have a small collection of digitized and downloaded Allpress wills that may be useful for your research.

Sources

Prickett, K. (2024). Face of Fenstanton Roman crucifixion victim revealed. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-cambridgeshire-67943596

Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire, England, Church of England Baptisms, Marriages and Burials, 1538-1812 on Ancestry

Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754-1950 on Ancestry

See Emily Randall’s Family Tree on Ancestry

Cambridge Chronicle and Journal, October 8, 1803

Huntingdon, Bedford, & Peterborough Gazette, March 17, 1838

Bishop’s Transcripts for Fenstanton, 1604-1854. FamilySearch Film #007562846, Item 2

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Protestation_Returns_of_1641%E2%80%931642

HL/PO/JO/10/1/91/127 Protestation Return - Huntingdon - Toseland Hundred - Fen Stanton. As of February 2026 this document is awaiting a new home at the UK National Archives. See https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/accessing-parliaments-archive-collections/

Stuff digital. (2020). https://www.stuff.co.nz/entertainment/121275446/kiwi-actor-bruce-allpress-dies-aged-89