Charles Randall (1784-1849) of Huntingdon, England, was an only child, rare for the Georgian era. His father Charles Randall (1757-1795) and mother Catherine Ross (1759-1809) were both born in Huntingdon to large families. The couple married on 14 Jul 1783 at St James Piccadilly church in London by banns.(1) I don’t know how long they had been in London or in what capacity. They returned to Huntingdon to have their first and only child. In 1795 Charles the elder was appointed keeper of the Huntingdon County gaol in the office vacated by the death of his older brother, but a few months later he died suddenly at the age of 38.(2) His wife Catherine never remarried and neither of them left a will.

Charles Randall was baptised at All Saints Church in Huntingdon on 31 August, 1784 (photo taken in September, 2022)

Career

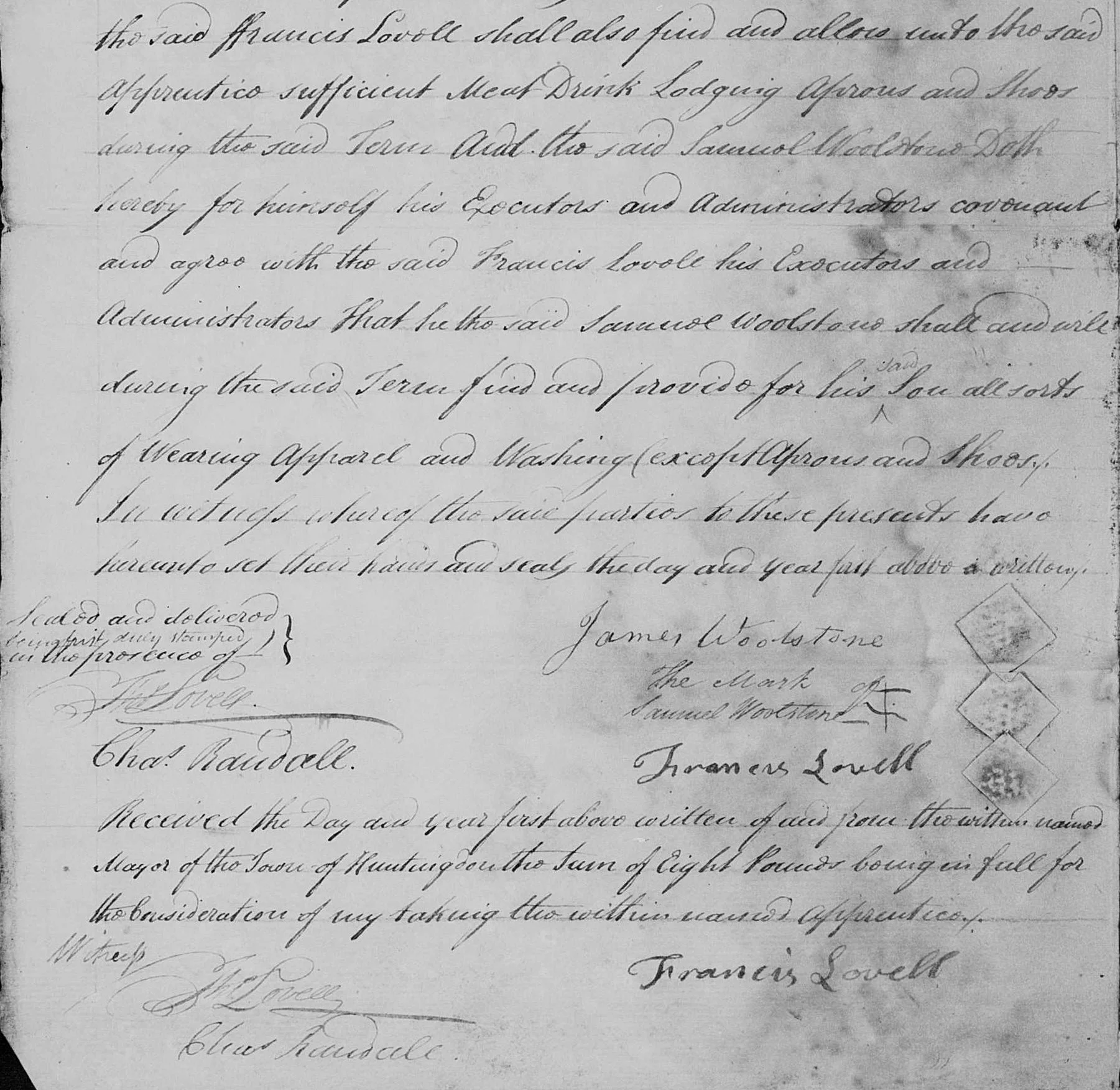

Charles and his widowed mother had several family members close by to rely on, but nevertheless Charles went to work at a young age, first as a scrivener, or someone who wrote and copied legal documents. This excerpt from an indenture (contract) of apprenticeship shows his penmanship and work as a scrivener in 1800, when he was just 16 years old.(3)

An excerpt of Charles’s work as scrivener, from Huntingdon Borough records

Charles is later recorded as being a surveyor of taxes (a tax assessor) and a solicitor’s clerk (a law clerk). Recently, I discovered that he also sold lottery tickets and shares for Richardson, Goodluck, & Co. His name appears in multiple newspaper advertisements from 1812 to 1816 as the Huntingdon point-person for the London company.(4) I assume he earned a commission for each ticket or share sold.

For these lines of work, Charles must have been skilled in reading, writing, and arithmetic. I imagine he was detail-oriented, thorough, and very knowledgeable about the people and places around town.

Ad in the Cambridge Chronicle and Journal, and Huntingdonshire Gazette, 10 March, 1815

Family

Charles was married and widowed twice, first to Mary Pattison and then to Mary Ann Allpress. I wrote previously about these marriages and about the confusion between his two wives. I also covered his children in depth, as follows:

Henry Randall (1807-1876, died in Huntingdon)

Charles Randall (1814-?, joined the Royal Marines, death date and location unknown)

John H Randall (1817-1869, died in London)

Mary Ann Randall (1819-?, moved to Missouri then Illinois, USA, death date unknown)

Edward Randall (1821-?, moved to Australia, death date unknown)

Frederick Randall (1822-1885, died in Australia)

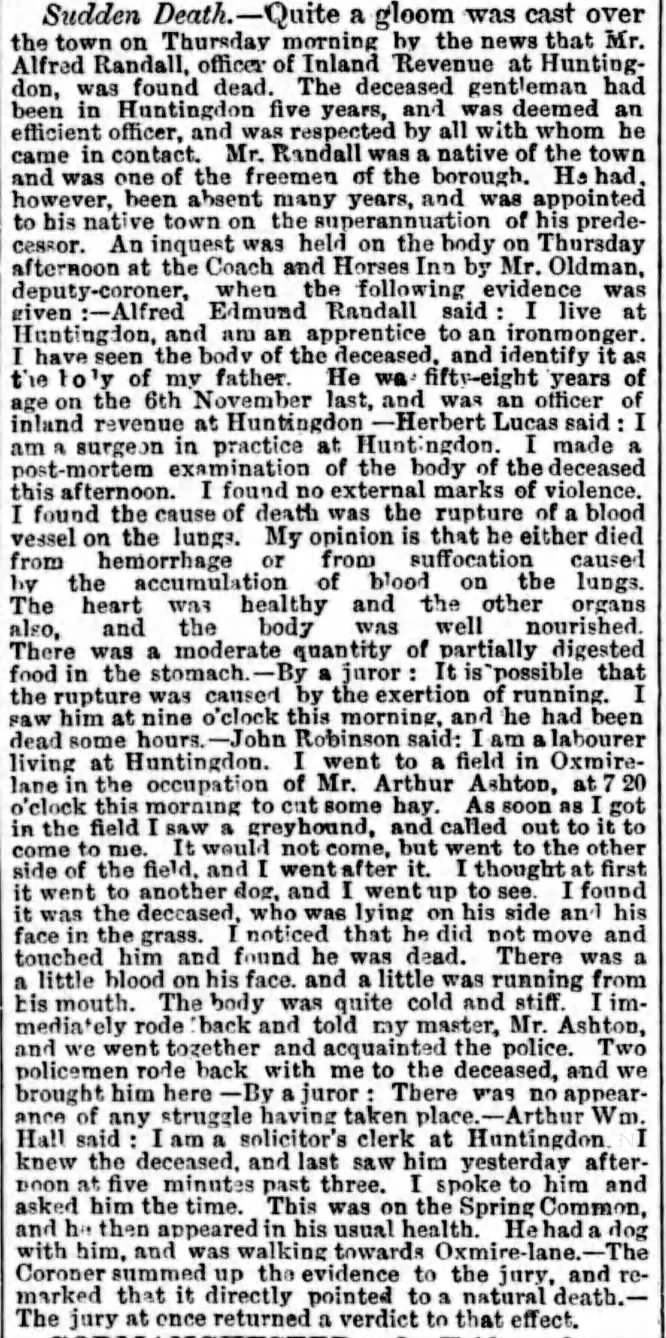

Alfred Randall (1823-1882, moved to another part of England then returned to Huntingdon, died in Huntingdon)

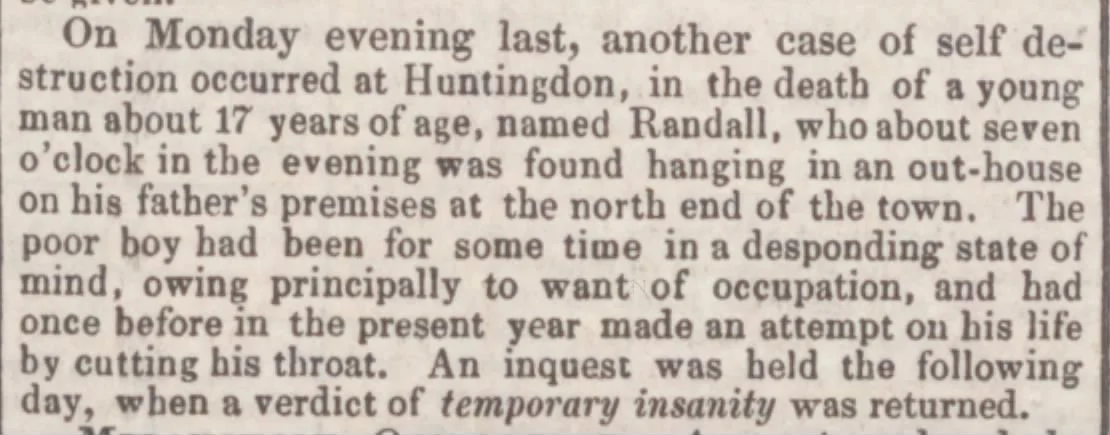

William Randall (1825-1843, died in Huntingdon)

Philip A Randall (1827-1895, died in Illinois, USA)

It seems that Huntingdon was a good place to raise a family in the early 19th century. In his book Rural Rides, published in 1830, William Cobbett wrote “Huntingdon is a very clean and nice place, contains many elegant houses, and the environs are beautiful. Above and below the bridge, under which the Ouse passes, are the most beautiful, and by far the most beautiful, meadows that I ever saw in my life. … All that I have yet seen of Huntingdon I like exceedingly. It is one of those pretty, clean, unstenched, unconfined places that tend to lengthen life and make it happy.”(5) This glowing review was based on observations made by Cobbett in 1822. By the middle of the century, many of the Randalls had left Huntingdon and moved elsewhere.

Civic Engagement

Throughout his life, Charles was active in town affairs, serving on juries and attending local government meetings. In 1805, at the age of 21, he was admitted as a burgess of Huntingdon.(6) A burgess was considered one of the freemen of the borough, and was one of a limited number of men allowed to vote in municipal and parliamentary elections. Other privileges included access to common lands (aka commons) for the grazing of livestock.

For centuries, Huntingdon was under the control of the Montagu family, who held the title Earl of Sandwich. By the late 1820s many freemen had become “disaffected” over town debts, misuse of funds, management of the commons, and the sale of freedoms (i.e., freemen status) to nonresidents.(7) The following newspaper report on a Borough meeting in 1827, at which Charles served as Chairman, highlights the concerns of the burgesses.(8)

From the Huntingdon, Bedford, & Peterborough Gazette, 29 Sep, 1827 (This is a truncated version of the full article)

These tensions continued into 1829, when Charles chaired another meeting of the burgesses, in which committee members voiced their opposition to the non-resident burgesses newly admitted by the Lady Sandwich. The committee bemoaned the "corruption of the elective franchise" and "the misapplication of charity funds."(9) Charles took a leading role in addressing these perceived injustices, but I was not able to find much evidence of his involvement after this point. This may be due to the death of his wife in 1830 or to various national reforms passed in the 1830s.

From the Huntingdon, Bedford, & Peterborough Gazette, 29 Aug, 1829

In 1835, Charles sought the appointment of Relieving Officer for the newly formed Huntingdon Poor Law Union.(10) The duties of such an officer were to receive applications from paupers seeking relief and to “examine the merits and circumstances of each case.” In cases of urgent need, the officer could grant temporary relief by giving the pauper “articles of absolute necessity” or by placing the pauper in the workhouse. The Relieving Officer reported weekly to the Board of Guardians. Charles was not selected; the role went to another gentleman.(11) But I enjoyed reading his “campaign ad” in the newspaper:

From the Huntingdon, Bedford, & Peterborough Gazette, 21 Nov, 1835

A series of UnfortunAte Events

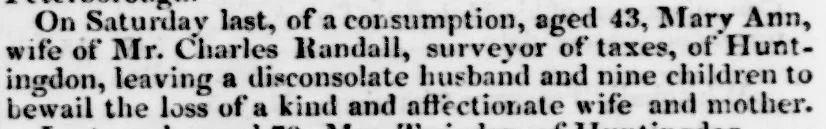

Although Charles was blessed with many children and seemed to be in good social standing, he undoubtedly suffered after the death of his wife Mary Ann (née Allpress) in 1830. The newspaper report of her death describes Charles as “disconsolate.”(12) He was left with 9 children to care for, ranging in age from 3 to 23. He did not remarry.

From Drakard's Stamford News, 14 May, 1830

The next year, Charles’s house was broken into. The thieves stole coins, a silk-lined coat, shawls, silver spoons, tea, and sugar.(13) Then, in 1843, Charles lost his teenage son William to suicide.(14)

Charles died in 1849 from a “diseased liver.”(15) This cause of death suggests (but does not confirm) that Charles was an alcoholic. He was buried in the parish of All Saints with St John. It does not seem that a headstone survives for him or for either of his wives.

His will, written in 1842 and proved soon after his death at the Prerogative Court of Canterbury in London, was very short and anticlimactic.(16) He named his son John Randall as executor, but his son Henry ended up handling the sale of his estate. Henry posted a notice in the newspaper announcing the sale of one lot with two dwelling houses in Huntingdon, and two lots (well-planted with fruit trees) in the neighboring village of Brampton.(17) The properties sound lovely, but unfortunately I have not been able to figure out exactly where they were located.

From Cambridge Weekly News, 21 Apr, 1849

I am very lucky to have an ancestor who made it into the local paper on so many occasions, offering valuable insights into his life. I also appreciate the work of the Huntingdonshire Archives in preserving and making available the historic documents that mention my ancestors. I hope you have enjoyed this “deep dive” into my 4th great-grandfather Charles Randall and this peek into early 19th century Huntingdon.

Sources

Westminster, London, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754-1935

Cambridge Chronicle and Journal, 21 Nov, 1795, pg 3

Records of Huntingdon Borough, 1350-1866 (Apprenticeship Indentures). FamilySearch.org Film #008869032 Item 23.

Cambridge Chronicle and Journal, and Huntingdonshire Gazette, 10 Mar, 1815, pg 1

Corbett, William. (1830). Rural rides (Project Gutenberg ebook).

Huntingdon Court Records, 1797–1835 (Freemans Rolls). FamilySearch.org Film #008482829 Item 1.

The History of Parliament: Huntingdon (1820-1832) at https://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1820-1832/constituencies/huntingdon

Huntingdon, Bedford, & Peterborough Gazette, 29 Sep, 1827, pg 3

Huntingdon, Bedford, & Peterborough Gazette, 29 Aug, 1829, pg 3

Huntingdon, Bedford, & Peterborough Gazette, 21 Nov, 1835, pg 3

Cambridge Chronicle and Journal, and Huntingdonshire Gazette, 8 July, 1836, pg 3

Drakard's Stamford News, 14 May, 1830, pg 3

Huntingdon, Bedford, & Peterborough Gazette, 22 Jan, 1831, pg 3

General Record Office. Death certificate for William Randall, 10 July, 1843

General Record Office. Death certificate for Charles Randall, 1 April, 1849

England & Wales, Prerogative Court of Canterbury Wills, 1384-1858: Charles Randall, probate 14 April 1849.

Cambridge Weekly News, 21 Apr, 1849, pg 1