In a previous post, I wrote about my great-great-great-grandfather John Henry Randall (1817-1869) and the ladies in his life (the Beresford sisters). John Henry was the second child of Charles Randall (1784-1849) and Mary Ann Allpress (1786-1830) of Huntingdon, England. He usually just went by John and should not be confused with his older half-brother Henry Randall, the Huntingdon schoolmaster. John was the only one of his siblings to settle permanently in London. Here I delve more into his career in law enforcement in Victorian London.

Illustration of a policeman or “Peeler” as they were called (c1840), from the collection of the London Museum. The early uniforms were blue and included top hats as shown here. The rounded Custodian Helmets that we now associate with British police were introduced later. (1)

Career with the London Metropolitan Police

When John Randall married Mary Ann Beresford in 1841 in Huntingdon, he was working as a grocer. (2) A few years later, the couple moved to London and settled in the neighborhood of Bloomsbury. This area is home to the British Museum and University College London and is known for its elegant and understated Georgian architecture. Charles Dickens lived in Bloomsbury for several years, first on Doughty St and later at Tavistock House.

John and Mary Ann had two sons, both of whom died at a young age. The first son lived just 11 weeks. On the child’s 1846 death certificate (3), John gave his occupation as “police constable” and his residence as 15 Leigh St in the district of Grays Inn Lane.

With some digging, I learned that John joined the London Metropolitan Police (abbreviated as MEPO) in 1845. Police forces were fairly new at the time, having been established by Sir Robert Peel in 1829. (4) I have not been able to find John’s swearing-in or sign-on papers, but I did find him listed in record set MEPO4/334 at The National Archives. (5) These records are a bit confusing to navigate, and they are not indexed. But by browsing the records page by page, I found “my” John Randall in file MEPO-4-334_5.

John Randall is listed on the last line of this excerpt from MEPO-4-334_5 at The National Archives

This record set is a collection of warrant (appointee) numbers issued to new recruits, listing their name, date of appointment, date of removal, and the names of two references. John’s warrant number was 21912. He was appointed on 17 March, 1845, and dismissed on 27 September, 1859. A subsequent page shows that he was recommended by his father-in-law William Beresford and by the Rev. John Fell of Huntingdon.

Police recruits were required to be at least 5’7” in height and generally fit and healthy. Constables worked 6 or 7 days (or nights) a week and walked 10 or more miles each day on foot patrol. (1, 4)

Max Schlesinger wrote about the London policemen he encountered in the early 1850s, describing their work as dealing with “the vulgar sins of larceny, robbery, murder, and forgery” and taking care of “drunkards and of children that have strayed from their homes.” (6) Schlesinger argued that the London police were successful in reducing crime and cleaning the streets because they were such keen observers; they would investigate anything that looked unusual or out of place. He wrote:

The London policeman … knows every nook and corner, every house, man, woman, and child on his beat. He knows their occupations, habits, and circumstances. This knowledge he derives from his constantly being employed in the same quarter and the same street, and [from that] platonic and friendly intercourse which he carries on with the female servants of the establishments which it is his vocation to protect. … The handsome policeman, too, with his blue coat and clean white gloves, is held in high regard and esteem by the cooks and housemaids of England. His position on his beat is analogous to that of the porter of a very large house; it is a point of honour with him, that nothing shall escape his observation.

I have to believe that John Randall was a competent police man, as he served the MEPO for 14 and a half years. I don’t have any indications that he was ever promoted to a higher rank. He was always recorded as a constable. But in 1859 he was dismissed for unknown reasons.

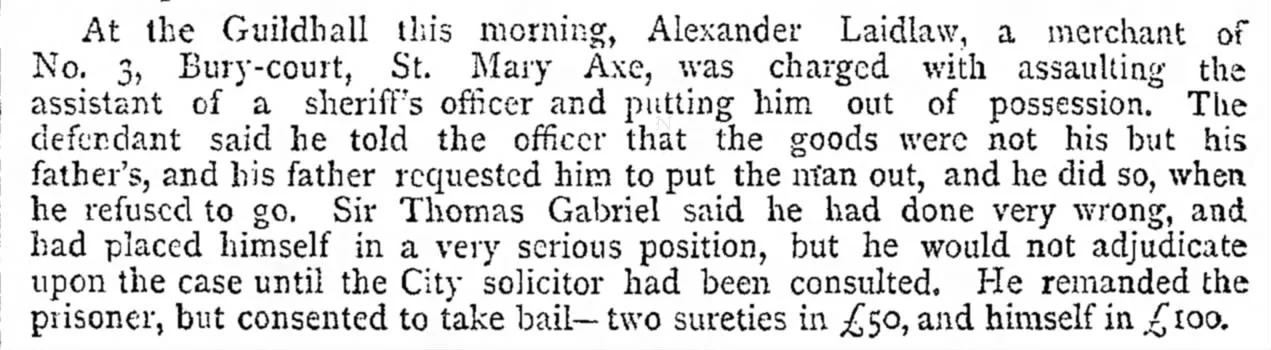

Common causes for dismissal were drunkenness and insubordination. Other policemen became “worn out” and resigned at an early age (1). My ancestor may have been injured on the job and unable to resume his duties in a satisfactory manner. I can’t know for sure, but I believe the police constable mentioned in the following article from May 1859 is “my” John Randall. (7)

Article from The Globe, 25 May, 1859

I couldn’t find any more details for this case, such as the location of the crime or the full court proceedings. But if this is my John, it means he was let go from the police force at age 42, after being injured on the job, without a pension. Yikes. According to Green et al. (2024), receipt of a police pension during this time period was “at the discretion of the employers.” (8) Maybe John engaged in misconduct after his injury or maybe his superiors weren’t very fond of him?

In 2022 I reached out to the Metropolitan Police Museum and Archive via the contact form on their website to see if they had any additional files on my ancestor. The response I received from the Curator was rather discouraging. Her exact words were “We don't have service records for officers from these dates.” That doesn’t make sense, because their website says they hold Police Orders starting in 1857, and I inquired about records up to 1860. Maybe I’ll contact the Police Museum and Archive again and word my question differently.

Life after dismissal

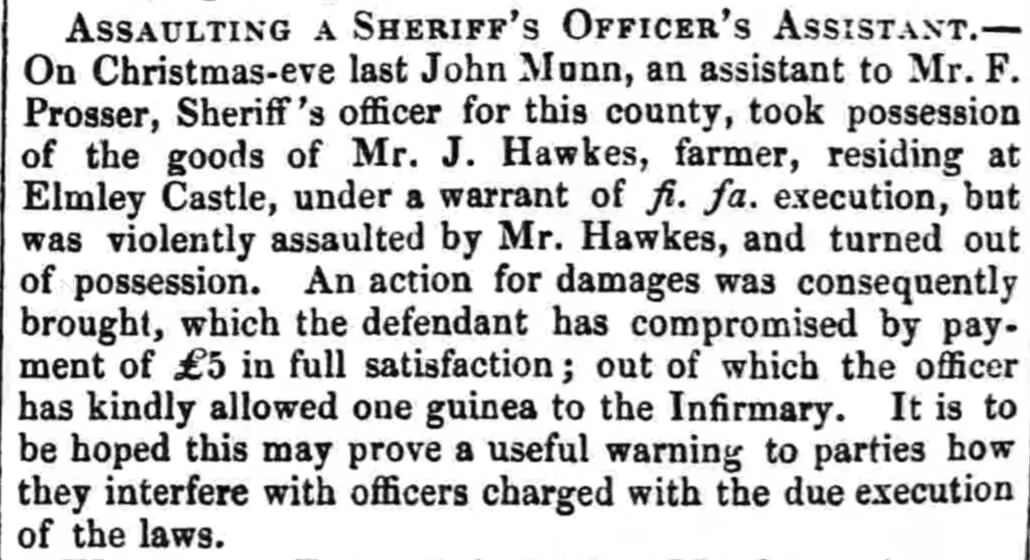

After being fired from the London Metropolitan Police, John remained in Bloomsbury and began working for a Sheriff’s officer. (This would have been an officer for the county of Middlesex). In 1864, John’s wife Mary Ann died. On her death certificate his occupation reads “Assistant to Sheriff’s officer.” (9) Three years later, John had a son with Mary Ann’s sister Rhoda, who had been deserted by her husband William Ashman. At this time, his occupation was recorded as “Sheriff’s officer’s servant.” (10) In 1868, when daughter Bessie Jane was born, John’s occupation was listed as “Sheriff's officer's possession man.” (11) This version of the job title is the most insightful, as it indicates that he was involved in debt collection, asset seizure, and repossession of goods. In other words, he was a “repo man.”

The following court cases from the era mention other sheriff’s officer’s assistants and highlight the duties and dangers of the job:

The Pall Mall Gazette, 11 Aug, 1869 (12)

Berrow's Worcester Journal, 16 Feb, 1856 (13)

One of Charles Dickens’s characters had a similar occupation, although Dickens refers to him as a “broker’s man.” In Chapter 5 of Sketches by Boz, Dickens writes about a man named Mr Bung whose work involved serving a “warrant of distress” to the head of a household and staying in the house until he was given the money owed. (14) Through this fictional character, Dickens paints a clear picture of what this job entailed. Mr Bung narrates:

A broker’s man’s is not a life to be envied... But what could I do, sir? The thing was no worse because I did it, instead of somebody else; and if putting me in possession of a house would put me in possession of three and sixpence a day, and levying a distress on another man’s goods would relieve my distress and that of my family, it can’t be expected but what I’d take the job and go through with it. I never liked it, God knows; I always looked out for something else, and the moment I got other work to do, I left it. … it’s the being shut up by yourself in one room for five days, without so much as an old newspaper to look at, or anything to see out o’ the winder but the roofs and chimneys at the back of the house, or anything to listen to, but the ticking, perhaps, of an old Dutch clock, the sobbing of the missis, now and then, the low talking of friends in the next room, who speak in whispers… or perhaps the occasional opening of the door, as a child peeps in to look at you, and then runs half-frightened away—it’s all this, that makes you feel sneaking somehow, and ashamed of yourself… If they’re very civil, they make you up a bed in the room at night, and if they don’t, your master sends one in for you; but there you are, without being washed or shaved all the time, shunned by everybody, and spoken to by no one, unless some one comes in at dinner-time, and asks you whether you want any more, in a tone as much to say, “I hope you don’t.”

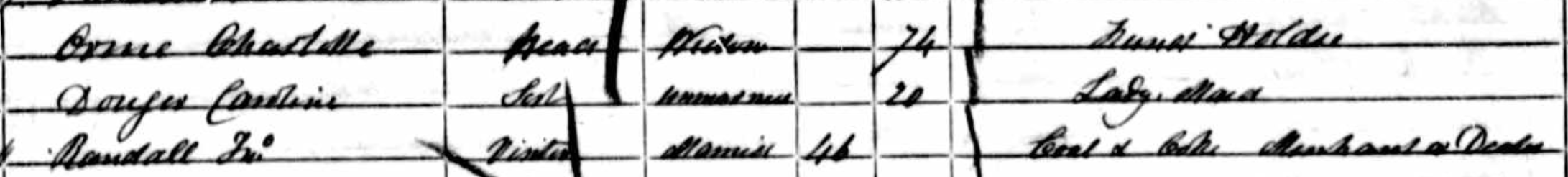

It is wild to me that a possession man would have stayed at the home of a debtor until he was paid. But this explains John Randall’s weird 1861 Census record. In this Census, taken on the night of Sunday, April 7th, 1861, John’s wife Mary Ann was enumerated solo, as a married dressmaker residing at 44 Burton St in Bloomsbury/St Pancras. (15) Meanwhile, John was enumerated 4.5 miles to the west at 9 Napier Rd in Kensington. His marital status was given as married and his occupation was recorded as “coal and coke merchant and dealer.” I have no other records of him with this occupation, and I don’t think he ever had this occupation. But this is definitely him, as his birthplace is listed as Huntingdon. The head of the household was a 74-year-old widow named Charlotte Orme, and the only other resident was a 20-year-old lady’s maid. (16)

The 1861 Census record for 9 Napier Rd, St Mary Abbots, Kensington

At first I could not figure out what John was doing at this house. I could not find any connection between my family and that of Charlotte Orme or her maid. At first, I thought John was “stepping out” on his wife. Would that result in this Kensington sleepover? Highly unlikely. I now realize that John was there as a “possession man.” To save face and avoid being outed as a debtor, the widow Orme got creative on her Census form to hide the true occupation of her unwelcome visitor. Thanks to Dickens, I was able to solve this case and gain insight into this chapter of my ancestor’s career.

Death

John Randall continued with his repossession work until his death on March 26, 1869 at University College Hospital. His death certificate suggests that he was a smoker, as his causes of death were bronchitis, emphysema, and heart disease. (17) Although this record gives his age as 53, he was only 51. He left behind 2 young children (John Harry and Bessie Jane) who eventually moved to Ludlow, Massachusetts.

John was buried at St Pancras cemetery in East Finchley, North London. According to cemetery records, he received a third class, unconsecrated burial. (18) There is no sign of a will or probate for him, suggesting that he did not have any money to leave behind at his death.

I visited St Pancras cemetery in May 2025. Despite having the plot number (Square 10 H, Number 52), I couldn’t find John’s gravesite. That part of the cemetery is overgrown with ivy, the section boundaries are unclear, and the stones are crumbling and eroded. (I also saw a fox at one point.) It’s possible John never had a headstone. He may have only had a wooden cross or small stone marker on his grave. At least he’s somewhere green and peaceful.

John is buried somewhere in this general area of St Pancras cemetery (photo taken May 2025)

The billy club

I can’t forget to mention the billy club. This wooden artifact has been passed down in the Randall family of Ludlow, Massachusetts, for several generations, with the suggestion that it came from England, but a more detailed story of its origin has been lost. Some might call this a truncheon or baton, but in our family we’ve always called it a billy club, which was the same term used for a truncheon in Victorian London (1). I doubt this particular club was issued by London MEPO, as it bears no markings or insignias, so maybe it’s a baton that John Randall used to protect himself when working for the sheriff’s office. Or maybe it came from John’s father-in-law William Beresford, who was a parish constable in Huntingdon for many years.

The Randall family “billy club”

Someday I’ll take the billy club on Antiques Roadshow to learn its true age and origin. Until then, the club evokes images of Victorian London, where police constables such as John Randall patrolled the streets, keeping a watchful eye out for thieves and other Dickensian characters lurking in the corners.

References

Czerny, V. (2017). Peelers: The police force under the reign of Queen Victoria. Available for download at The Ragged Victorians.

1841 England Census for St John parish, Huntingdon

General Register Office. Death certificate for Charles William Beresford Randall, 28 May, 1846

The National Archives (UK). Crime and Punishment: Robert Peel

The National Archives (UK). Record set MEPO4/334: MEPO-4-334_5, pg 73.

Schlesinger, M. (1853). Saunterings in and about London (O. Wenckstern, Trans.). London: Nathaniel Cooke. [Project Gutenberg ebook]

The Globe, May 25, 1859, pg 4

Green, D., Brown, D., Smith, H., Chick, J., & Preger, N. (2024). Managing the police workforce: Sickness and pensions in the Metropolitan Police in late nineteenth-century London. Business History Review, 98(2), 417–446. doi:10.1017/S0007680524000278

General Register Office. Death certificate for Mary Ann Randall, 17 Dec, 1864

General Register Office. Birth certificate for (John) Harry Ashman Randall, 8 Jan, 1867

General Register Office. Birth certificate for Bessie Jane Randall, 17 Dec, 1868

The Pall Mall Gazette, Aug 11, 1869, pg 9

Berrow's Worcester Journal, Feb 16, 1856, pg 5

Dickens, C. (1903). Sketches by Boz. London: Chapman & Hall. (Original work published 1839) [Project Gutenberg ebook]

1861 England Census for St Pancras, Marylebone

1861 England Census for St Mary Abbots, Kensington

General Register Office. Death certificate for John Randall, 26 Mar, 1869

Deceased Online. Burial register entry for John Randall, 2 Apr, 1869, St Pancras Cemetery.